- Our School

- Our Advantage

- Admission

- Elementary•Middle School

- High School

- Summer

- Giving

- Parent Resources

- For Educators

- Alumni

« Back

Stress and Anxiety: An Overview and Strategies for Mitigation

October 17th, 2018

This is the first post in a five-part series about students, stress, and anxiety. The first article is an overview of anxiety, the second article looks at a relaxation program for elementary and middle school students, the third discusses how a student learned to manage her anxiety, the fourth explores how mindfulness can reduce anxiety, and the fifth covers the relationship between language-based learning disabilities and anxiety.

By Jerome Schultz, Ph.D.

Most children will experience some form of stress or anxiety during childhood. Temporary stress and anxiety are normal and typically harmless, but more severe forms can have a lasting toll.

I’d like to use this blog as an opportunity to talk about what stress is, how it’s related to anxiety, and what happens to the brain and body during stress. I also want to differentiate between good stress and bad (or toxic) stress, how to use the former, and how to prevent or reduce the latter. Finally, I’ll offer simple but effective strategies that cost nothing, take little time, and have a powerful impact on mental health and learning in kids of all ages.

Most of my writing, webinars, and keynote addresses over the past decade have focused on the impact stress has on learning, emotions, and behavior in students from preschool (yes, unfortunately!) through college. I’ve come to believe that stress is one of the most important factors underlying efficient learning and also one of the most under-recognized impediments to successful and joyful learning (and teaching!). Teachers and parents both express their concern about an apparent increase in stress in children and young adults. This troubling observation is confirmed by recent research. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, about 32% of adolescents have been diagnosed with anxiety, and a little more than 8% have what’s regarded as a severe impairment. It has been my experience that when adults have a better understanding of this complex human reaction, they can teach kids how to recognize, reduce, and use stress as the fuel for success.

What is stress?

Stress is the reaction of the body and brain to situations that put us in harm’s way. The stressor may be a physical threat (e.g., a baseball coming quickly toward you) or a psychological threat (e.g., a worry or fear that you will make a mistake delivering your lines in a play or write a passage that won’t make sense to the reader). Stress, or more specifically, the stress response, is our body’s attempt to keep us safe from harm. It’s a biological and psychological response. When we’re under stress, the chemistry of our body and our brain (and, therefore, our thinking) changes. A part of the brain called the amygdala does a great job learning and remembering what’s dangerous, and it tries to help us avoid those things as we move through life.

How can stress be good and bad?

All human and non-human animals have the built-in capacity to react to stress. You may have heard of a “fight or flight” response. This means that when faced with a threat, we have three basic ways of protecting ourselves. We can run away (flee), stand firm (freeze), or try to overcome or subdue the threat (fight). When we have a sense that we can control or influence the outcome of a stressful event, the stress reaction works to our advantage and gets our body and brain ready to take on the challenge. That’s good stress; at the most primitive level, it keeps us alive. It also allows us to return to a feeling of comfort and safety after we have been thrown off balance by some challenge and overcome it.

On the other hand, bad stress occurs in a situation in which we feel we have little or no control over the outcome. We have a sense that no matter what we do, we’ll be unable to make the stressor go away. Body and brain chemistry become over-reactive and get all out of balance. When that happens, it can give rise to another protective mechanism—to “freeze” (like a “deer in the headlights”). We can freeze physically (e.g., become immobilized) or we can freeze mentally (e.g., “shut down”). In these situations, the stressor wins and we lose because we’re incapacitated by the perceived threat. Think about it this way:

Navy SEALs face high-threat situations. They also have skills to deal with just about anything that comes along. As a result, these men and women don’t have a lot of anxiety. Their coping skills give them a sense that they can handle anything that comes along. This makes it easy to understand their motto: "The Only Easy Day Was Yesterday." Kids who do not have (or who don’t believe they have) sufficient coping skills are often highly anxious.

What is anxiety?

Anxiety comes in many forms. It can be situational (that is, specific to one kind or class of worry, like traveling or being in social situations). Kids who have not had a lot of success in school may experience marked anxiety in situations in which they feel they will make mistakes, be ridiculed, or made to feel foolish in front of others. Children and adults who have been exposed to early trauma, extreme neglect or abuse (sometimes referred to as Adverse Childhood Events, or ACEs) are more likely to experience anxiety.

When the anxiety is specific to or triggered by the demands of being with or interacting with people and is characterized by a strong fear of being judged by others and of being embarrassed, it is known as social anxietydisorder (or social phobia). This fear can be so intense that it gets in the way of going to work or school or doing everyday activities. Children and adults with social phobia may worry about social events for weeks before they happen. For some people, social phobia is specific to specific situations, while others may feel anxious in a variety of social situations.

Anxiety can also be generalized (that is, a kind of free-floating sense of worry or impending trouble that doesn’t seem to be specific to one trigger or event). In its more serious form, this is considered a psychiatric disorder known as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

What’s the relationship between anxiety and stress?

Simply put, anxiety is a state of worry about what might be—as compared to stress, which is a reaction to what is. If you take the stressor (i.e., the threat) and subtract from that your coping skills, you get anxiety. Both stress and anxiety trigger the same chemical reactions in the brain, which does a really good job remembering negative experiences. If you worry all the time about something bad happening to you, that puts you in a state of chronic stress.

What’s the connection to stress and learning disabilities?

Stress and anxiety increase when we’re in situations over which we have little or no control (a car going off the road, tripping on the stairs, reading in public). All people, young and old, can experience overwhelming stress and exhibit signs of anxiety.

Children, adolescents, and adults with a learning disability, such as dyslexia, are particularly vulnerable to stress and anxiety. Often, it’s because they may not fully understand the nature of their learning disability. As a result, they may blame themselves for their own difficulties. Years of self-doubt and self-recrimination may erode a person’s self-esteem, making them less able to tolerate the challenges of school, work, or social interactions and more stressed and anxious.

For example, many individuals with learning disabilities have experienced years of frustration and limited success, despite countless hours spent in special programs or working with specialists. Their progress may have been agonizingly slow and frustrating, rendering them emotionally fragile and vulnerable. Some have been subjected to excessive pressure to succeed (or excel) without the proper support or training. Others have been continuously compared to siblings, classmates, or co-workers, making them embarrassed, cautious, and defensive. When students understand the nature of their learning disability, and how to use specialized strategies to experience success, stress and anxiety can take a back seat to competence.

How can students move from distress to DE-STRESS?

A little bit of stress is a good thing; it keeps us on our toes and gets us ready for the challenges that are a normal and helpful part of living in a complex world. Yoga, mindfulness activities, meditation, biofeedback, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), medication, and exercise are among the many ways that individuals (with and without dyslexia) can conquer excessive or debilitating stress. For the individual with a learning disability such as dyslexia, effectively managing and controlling stress must also involve learning more about the nature of the specific learning disability.

Competence instills confidence, and competence leads to success. When children, adolescents, and adults are able to develop a sense of mastery over their environments (school, work, and social interactions), they develop a feeling of being in control of their own destiny. Control through competence is the best way to minimize the negative effects of stress and anxiety.

What to DO?

Let me offer you a couple of simple, but effective strategies to minimize stress in school:

Hurdles and Helpers: Have students think of some task that they did well and examine the factors that got in the way (hurdles) and those that led to success (helpers).

Example: A student who successfully learned to scuba dive can be asked to think of the factors that got in the way, e.g., a fear of suffocation, and those that enhanced that learning, e.g. the thrill of seeing the wonders of undersea life. Have students apply that same analysis to the task at hand. What gets in the way and what will increase their chances for success?

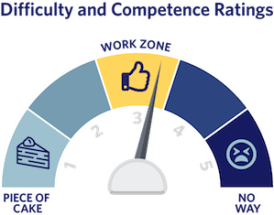

Difficulty and Competence Ratings: Have students rate (using a 1-5 scale) the perceived difficulty level of a task: 1= incredibly easy; 5 = “wicked hahd” (as they say up here in New England). Then have students rate their ability to do this task: 1 = “piece of cake”; 5 = “no way”. Enlightened teachers ask the student: “What can you or I do to make you think of this as a 'work zone' task?" (For example, level 3: a task on what I call “the cusp of their competence.”) This might mean putting pictures with the words, defining difficult words first, doing one math problem at a time, or having the information read to the student.

If a student says she has very little ability to do the task, but she has in fact done equally challenging tasks in the past, the teacher can pull out samples of similar, yet successfully completed work. By setting what I call “competence anchors” in this way, the student may approach the new task with an “I can” mindset. If so, this increases a sense of control, decreases anxiety and moves the student in the direction of success.

I hope that my comments here reflect both my concern about the impact of stress in the lives of kids, as well as my optimism that this “demon” can be tamed, its energy harnessed, and used to move kids from an “I can’t” frame of mind to “I can do this!”

About the Author

Jerome Schultz is a clinical neuropsychologist, author, and speaker who has provided clinical services to families, and consultation and staff development to hundreds of private and public schools in the U.S. and abroad during his 35 year career. He is the author of Nowhere to Hide: Why Kids with ADHD and LD Hate School and What We Can Do About It. Follow him on Twitter@docschultz.

Posted in the category Social and Emotional Issues.

.jpg?v=1652115432307)